At a purely game level, they don't add a problem-solving strategy to dungeon-crawling. While there are certainly approaches to game design that encourage a huge range of available classes (3rd Edition, Astonishing Swordsmen and Sorcerers of Hyperborea, and GLOG, for example), I contend that classes revolve more about generalized player strategy, with a secondary element of game-interaction preference. The more general the structure of classes in the game, the greater the amount of the game open to participation by all players: hyper-specialized niches leave players with naught to do much of the time. Given that, the classic trio of Wizard, Thief, Fighter provides a range of strategy and interaction:

|

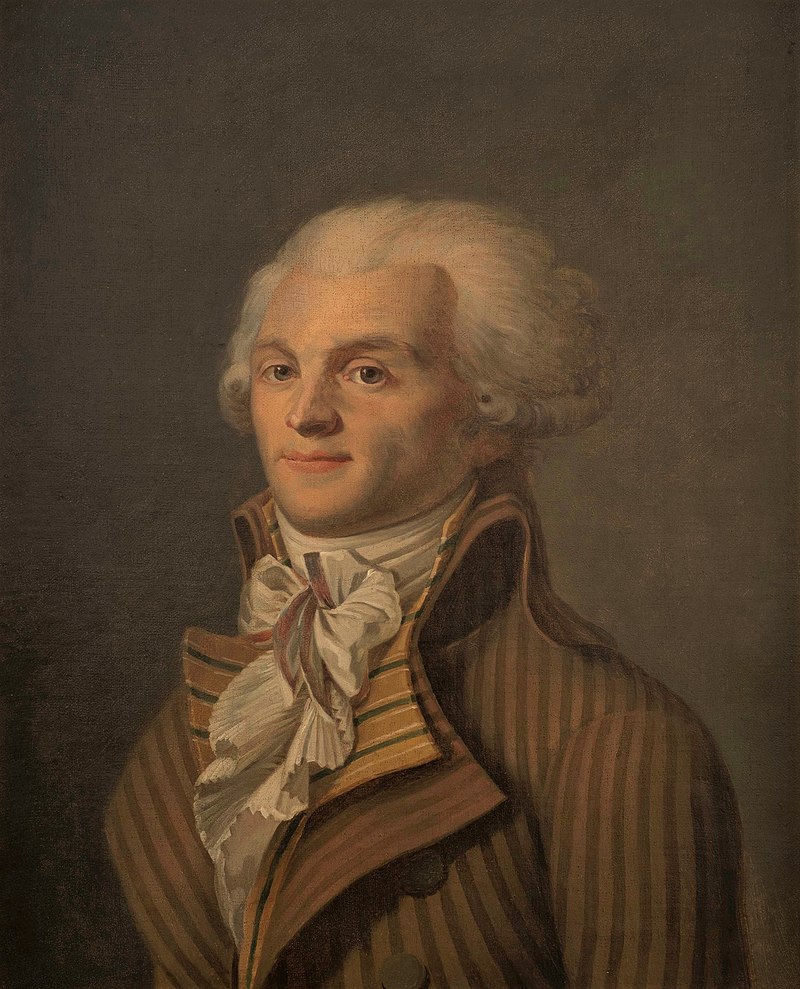

| Famously not a fan of clerics either. |

- Fighters provide a simple, brute-force approach to problems. They are best equipped to tackle situations with violence, in the sense of both dealing and resisting. Because of their greater toughness, they can take more risks than their companions. Their abilities are always "on".

- Wizards are for lateral thinking approaches. Their toolbox of spells opens them up to possibilities beyond the purely mundane. While later editions (and, to be honest, their origin in Chainmail) situates them more as artillery, they ideally serve to create new opportunities for the adventuring party. Their powers have finite uses.

- Thieves (which is a bad name, more on that later) are the finesse problem solver. They show up to the dungeon with a broader collection of skills than the fighter but less diverse than the wizard. In a sense they are a middle ground between two extremes, something made explicit in 1975's Tunnels and Trolls' Rogue class. More recent iterations have turned this archetype into an "Expert" with less attention granted to breaking-and-entering-type skills.